It’s the becoming that matters, not the destination. And we are always becoming.

For the audio version of this essay, please click on the recording below:

It is Tuesday evening, and I recently relapsed into depression. As in, within the last five days. My temperament leans heavily on the melancholic side, so I’ve told people—tongue in cheek—that I’m dysthymic. Meaning, just a little depressed.

The truth is, I’ve never fully recovered from the innards of depression since Auggie’s birth.

Now that the day is winding down, I’m ready to burrow myself under my comforter with a good book. The mental exertion of battling negative core beliefs and dark moods has left me depleted.

I collected my wits enough to join the family for our evening check-in, and now that it’s over, I can exhale in relief. Finally.

And yet, Felicity isn’t satisfied. She, at age thirteen, hurls recriminations at me, one after the other. A litany of invectives. Already feeling battle weary, these slay my heart. “Mom, you never listen to me. You don’t understand me. You don’t care about my problems…”

I don’t react, because if I do, I will detonate the sleeping bomb of rage inside me. I try to keep it quiet when depression strangles me.

So I sit here and take it, all of it. I want to call it verbal abuse, but I know she’s a teenager. I remember when I was her age, the friction between my mom and me a constant. I, too, felt my mom didn’t understand me or listen to me or care about my problems.

I don’t want to guilt trip Felicity into believing she’s responsible for my emotions. What I want is to be left alone, to stew in my misery until it passes. And I know it will pass eventually. Until then, I don’t want to injure anyone with my dismal thoughts.

Ben intervenes. “Felicity, we both are here to listen to—”

She interrupts. “No, no, it’s not you. It’s just Mom.” And she points her finger at me like a dagger in a duel. I don’t want to engage this, but I feel the bomb ticking now. “Right, right, it’s always me. I’m always the problem,” I say as if I’m also a child, storming into our bedroom and slamming the door behind me.

I can hear Sarah whimpering as I snuggle under the covers. She’s talking to Ben. “Dad, did I do something wrong? Is Mom mad at me?”

His response is muffled, but I think I know what he is saying: that no, it isn’t her fault and that mom just needs some space right now.

Next, a soft tap on the door. “Yes?” I ask. It’s Sarah. She opens it just a crack, peering inside my bedroom. I turn toward her. “You can come in, Sarah.” I try to keep my tone level, calm.

Her lip begins to quiver, and tears well in her eyes. “Mom, are you mad at me?”

My face softens, and I offer her a weak smile. “No, Sarah. You didn’t do anything. Why would you think that? I was upset at the way Sissy spoke to me, but I’ll cool off in here and talk to her about it later.”

Sarah hesitates before answering. “Why can’t things just go back to the way they used to be? Why is there always someone upset in our house? Why do I have to be the one who looks different?”

The downpour of questions cascades now. I don’t know which to answer first, so I interrupt. “I know it’s hard for you, Sarah. I’m sorry. I wish it were different. I don’t like all the conflict in our house, either. I try my best to deal with it, but everyone in our family seems to have really big emotions all the time.”

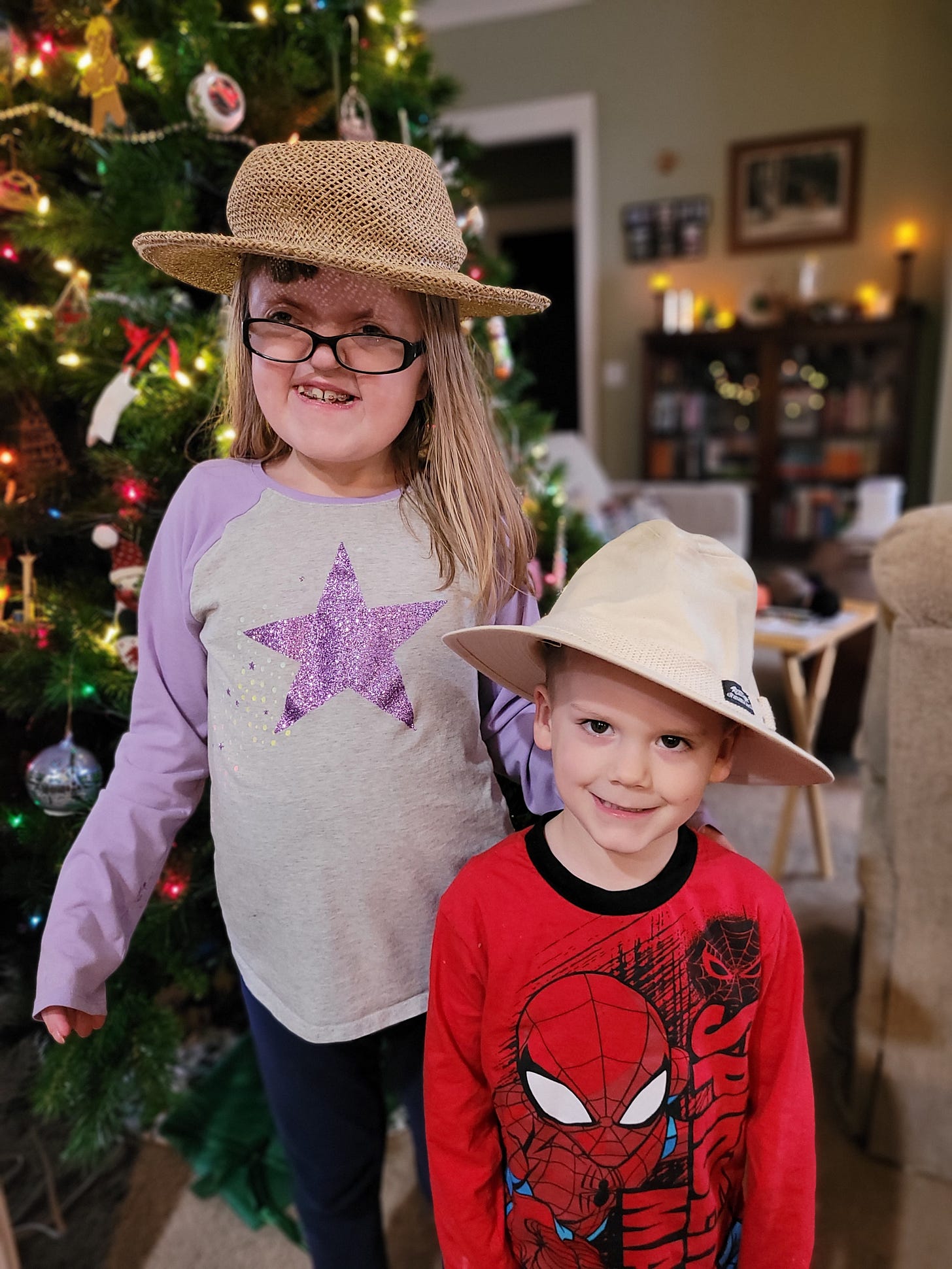

She blinks, teardrops trickling down her cheeks. “But why am I the only one who looks this way? Why can’t I look like everyone else in this family, or at school?”

I inhale deeply before replying. This one is tough. It’s a question that doesn’t have an answer, and there are a lot of those in my life. Probably in everyone’s life.

“I don’t know, Sarah. I wish I did, but I don’t. I know it’s hard for you to be different.”

“Is that bad?” she asks.

“No. Hard things aren’t always bad things. Every person on the planet has their own brand of hard, Sarah. We just don’t know what it is. Hard things can sometimes break us, but sometimes they make us stronger.”

“They do?” Her eyes widen, and she sniffles, wiping a tear from her eye.

“They can. But it’s okay if you struggle sometimes. You don’t have to go through hard things alone.”

Her face brightens. “Thanks, Mom. I love you.”

“I love you, too, Sarah.”

She turns away, slipping out of the door, which is still left slightly ajar. And I remember a metaphor one of my friends shared with me not long ago. That all the anxieties of life are these carbonated bubbles fizzing inside the mind and body, building pressure. And suddenly, the bottle comes uncapped, and all the excess carbonation spills out. What’s left has space to settle.

That’s what it feels like to live in this hurried world. It’s become an environment of constant pressure, and most days, I can’t contain it all. Now, my bubbles have fizzed over, and I can allow the carbonation room to calm itself. Something inside my body has finally uncorked, and I lean my head on my pillow, opening the cover of my library book.

Hard things don’t disappear. I know this, even as I escape into someone else’s life story. Mine will return as soon as I close the book. Even so, I’ve come to accept that not all problems have solutions, and I’ve stopped scavenging for them. My spirals don’t last as long in duration anymore. I can cut off the rumination over why and why not and remind myself that it’s okay to not know.

The unknown is terrifying, because it’s all a giant question mark, but that’s where most of us live, anyway. We dwell in the liminal space between hope and fear, straddling the fence between what once was and what is unfolding before us. There are nudges and inklings and glimmers that cue us on what direction to take, but we can never be certain if we got it right, if there is a right or wrong way. We just keep going.

That’s how we confront the hard things and reframe them. They aren’t bad or wrong. They’re just one aspect of the broader spectrum of human experience. To embrace elation means to accept hardships, too. When we lean into whatever is happening right in front of us and feel whatever surfaces, we give ourselves room to stretch, to elongate.

It’s the becoming that matters, not the destination. And we are always becoming.

I really liked this piece and I understand what Sarah is going through. When I was her age I also wanted to know why I had to be different and couldn’t look like everyone else. I wondered why I couldn’t go on certain field trips or had to get shuttled to the hospital more often than not.

I’m so sorry she has to go through this and (at the risk of sounding bold or too much) if she (or you) ever need someone to vent to, I’m always ready to listen. I may not know exactly what she’s going through but I’m sure her feelings were the same as mine way back when.

I think this is my favorite thing I’ve read of yours. I feel like I was in the room. It is so hard to navigate the challenges of kids and family and their unique struggles when you are neck deep in your own. Thank you for your vulnerability in this piece.