I have a confession to make

I used to be a branded Catholic author, but I quit three years ago.

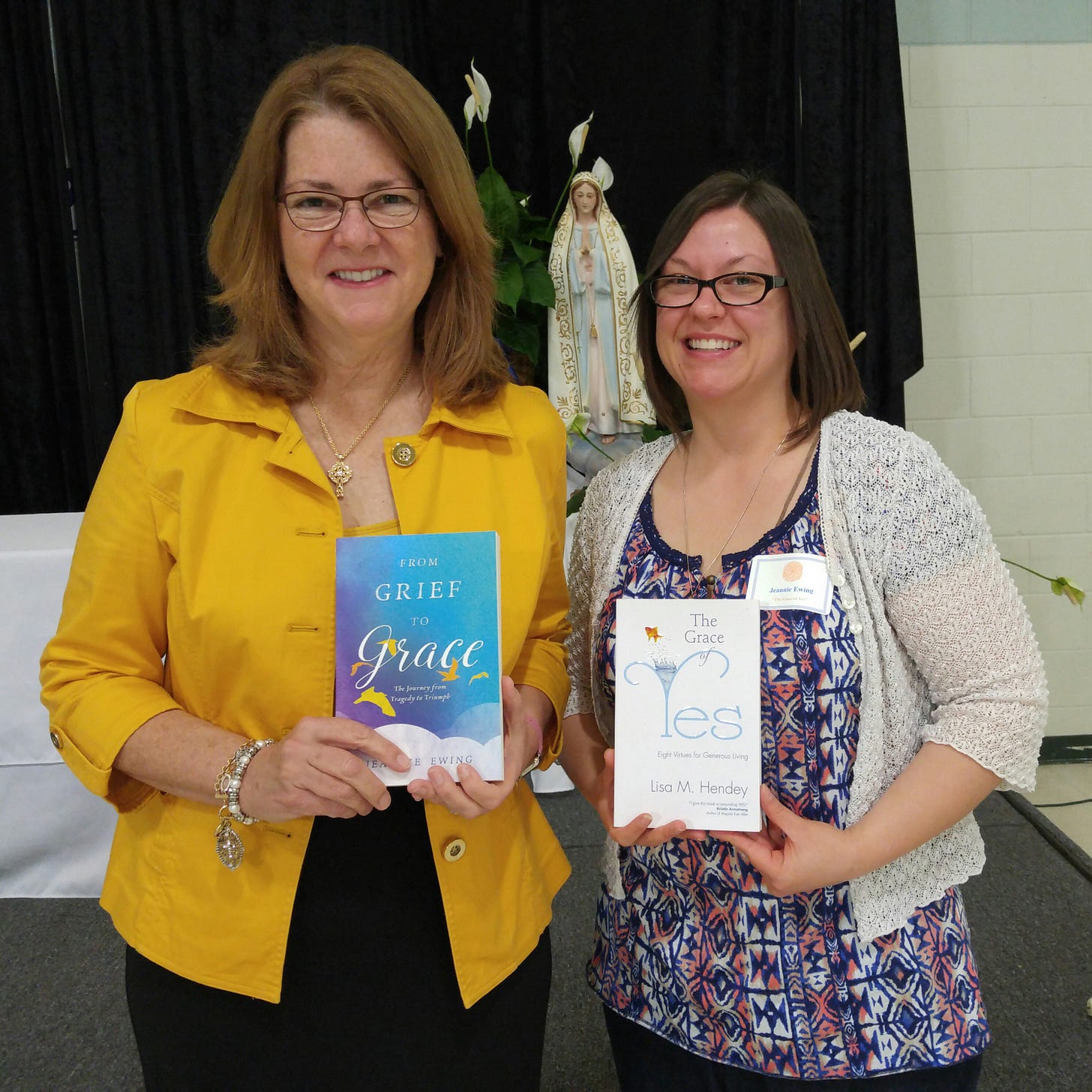

OK, so I’m taking a deep breath as I introduce you to the thematic thread of June’s weekly posts. I haven’t publicly written or spoken about my creative past—the fact that I once was a branded Catholic grief author who traveled nationwide to speak to the bereaved in workshops and retreats and conferences.

But two of my Substack friends,

and , independently of each other suggested that maybe I write about the thing I didn’t want to write about. Maybe I just work with the resistance and lean into it, then share whatever stories about my past want to be told through me.So there are five essays that take you into this world I left behind. This is the first one. I hope you will stay along for the ride.

In the comments, I’d love to hear about something you are embarrassed or ashamed of that you are ready to now share.

The Confession

I have a confession to make, and it’s been a long time coming: I used to be a branded Catholic author and speaker. Even as I write this, I find it ironic that I used the word confession in this way, because it’s not really something to be ashamed of. Yet I am. I’ve hidden it from you on Substack, because I’m afraid of the consequences this revelation might yield.

What if you unsubscribe?

What if you think I’m going to preach to you?

What if you believe I judge you secretly?

What if you hate Catholics?

What if you had a bad experience growing up in organized religion and can’t even read the word without feeling triggered?

All sorts of what ifs cloud my heart.

I’ll start at the end and go back to the beginning in separate essays, because there’s so much to say. And I’ve been careful (read: overly cautious) in what I publicly post about my experience, because religion is one of those hot-button topics that seems to elicit all sorts of colorful comments.

I’m not interested in debate. I’m equally uninterested in converting anyone.

What I want is to be here, among the rest of you, no matter who you are or what you believe (or don’t). I want to be valued for who I am and what I write today, and I want you to feel valued for who you are, too.

The Beginning of the end

Five years ago, I was collaborating with a well-known Catholic author (whom I will not name, for the sake of preserving his reputation) on a book for suicide survivors. He had written the first half, which summarized dense theology about what Catholics believe about suicide and where their souls go in the afterlife. To his credit, he was clear that those who die by suicide are not condemned to hell (no one is, actually) but are enfolded in the merciful arms of a loving God because of their mental and emotional torment.

My job was to write the second half of the book, because I was considered a grief expert at the time (more on that in a different essay). Untangling the complexities of grief—including the psychological and spiritual phenomena—meant that I needed to respect the nuances of bereavement without prescribing some panacea. That is tricky business, but I like a challenge. Also included in my portion of writing was interviewing a handful of suicide survivors and relaying whatever they wished to share about their stories.

As I interviewed each person, I learned that many had never before opened up in such a raw, honest way. Some raged at the God they thought they knew and understood. Others weren’t sure what they believed anymore. Some wrestled with various versions of faith that became more obscure over time. My response was to hold space for the expression of their grief and carefully construct a narrative that was true to what they felt.

Once I submitted my half of the book to the other writer (who made it plain that his name would appear on the book as the primary author, and mine would appear in tiny print underneath), he requested we speak on the phone. Immediately. Like, right then.

At the time, my youngest, Auggie, was still an infant. I was raising five kids and struggled with chronic sleep deprivation. Yet I resolved to fulfill my commitment to this book—which I believed was crucial to the conversations surrounding death (and still do)—so, yes, of course I dropped everything to speak to my co-author on the phone.

The discussion lasted five minutes, if you could even call it a discussion. He began with, “So, your half of the book isn’t going to be published.” When I asked why, he said, “Because the publisher said it needs a lot of edits.” Well, let me tell you a cold, hard truth: I was aware that the book would need edits, because every book requires revisions until it is polished. This was not the first book I’d written (I think it might have been number five at that point), nor the first time I’d collaborated with editors.

“So what’s going to happen to the work I’ve done?” I asked, and he said, “Well, you’ll still get paid, based on our contract, but I’m going to revert to my original draft, because that’s what the publisher wants.”

Okay. I can deal with getting paid if a project gets killed. It happens sometimes.

“But what about all the people who shared their stories with me? They believed by agreeing to open up publicly, they would be speaking to other suicide survivors so they would feel less alone.” This was the clincher for me. In my heart, I could not let these people down. They had poured so much of themselves into really hard, painful realities—including how their loved one died by suicide, who discovered their bodies, what the initial reactions were, how the family is doing now.

A short pause, and then he said, “I don’t know. That’s for you to figure out. I guess you’ll just have to tell them it’s not getting published.”

That was it. This had now become my responsibility to disappoint about six people who told me, “I’ve never said anything about this before. If it’ll help other people, I want to talk about it now.” Knowing their stories would be included in the book became their motivation for speaking up.

When I probed a bit further, my co-author said in a defensive tone, “I don’t owe you an explanation. We’re not publishing what you wrote.”

I don’t know for sure, but I had a hunch the entire time I crafted the stories for the second part of this book that the truth was too controversial for a Catholic publisher to take on. Questioning God? Raging at God? Not knowing if you believed anymore? Absolutely unthinkable.

Yet, to me, these were very natural experiences and made perfect sense. After all, I had grappled with all of these “problems of faith” and more after Sarah was born. It seemed healthy to revisit one’s original idea of God and faith and religion after a shocking, inexplicable event shakes their lives. How else does a person deepen their spiritual identity, if not to remain open and curious about what it all means?

One by one, I emailed the six suicide survivors to break the grim news. Every single one of them felt betrayed, and I told them they were right—it was unfair. The professional that I was (and am), I did not disclose the specifics, only that the publisher had decided not to move forward with what I had written and that I was deeply saddened at that choice.

The conclusion I made was this: The Catholic publisher was doing a grave disservice to not only the six contributors to the book but to the church community at large.

I felt devastated in knowing the compounded hurt these survivors felt, and I questioned my own beliefs and my creative identity. Unnerved, I took frequent walks to a local park, my thoughts swirling in a tempest. I offered the rhetorical question to no one in particular: “What am I supposed to do now? Why is this happening?”

And the response every time was, “You’re playing it too safe.”

It took me years to understand what this meant.

Today I want to showcase a generous and specific testimonial from one of my paid subscribers about why she chose to upgrade her subscription. It’s hard to describe spontaneously, but receiving this level of support is both an honor and quite humbling when you are starting out—or starting over, as in my case. Jean, thank you for your generous offering. And I want each of you who are reading with me today to know how much I value the time you choose to spend in my creative space online when I know you could be doing a host of other things. I hope you’ll find it’s worth it. Thanks for being here.

Your financial contribution helps supplement our family’s expenses and offset the costs of ongoing medical care for our daughter Sarah that requires 20 hours of unpaid caregiving on my part. I want you to know how much your support means and how it helps our family.

Hi Jeannie, I can appreciate your concerns about sharing your creative past. Thank you for honouring how that may be for your readers AND having the courage to take this as your next step. Congratulations for your previous successes and the knockbacks that enabled you to shed old skin and become the next iteration of who you are creatively, spritually, and humanly. Thankyou for acknowledging the compounded grief and betrayal the people you interviewed felt and for caring. In my humble opinion, that avenue was an opportunity for expression and that was great value, AND it wasnt the right portal for those stories to be published with integrity, grace, and compassion. Those stories yet exist and you continue to hold space for those brave, devastated, broken, and perhaps slowly healing family members. Thank you. I trust you will continue to deal honourably in your writing and living journey. Thank you for you.

@Ally Hamilton I just published this today and it goes along with our comment string from your latest essay, in case you’re interested. :)