I wrote the book I didn't believe I was equipped to write.

The invitation to write about grief was not what I wanted.

Before sharing this week’s post with you, I’d like to share one of my essays that was recently published in

called “Cries of Despair: A Birth Story Rewritten.” I hope you enjoy it, and feel free to share it with those you feel may be inspired or touched by it.The thematic element of this month’s posts center around a larger story about how I became an author and why I walked away to start over.

So there are five essays that take you into this world I left behind. This one is the third. I hope you will stay along for the ride. In today’s piece, I write about the serendipitous events leading up to my first traditionally published book called From Grief to Grace.

In the comments, I’d be delighted to hear about moments of serendipity in your own life.

Here is the second essay if you missed it last week:

2014

When I share with a few close friends and family members that I am blogging for two websites now—Catholic Mom and Catholic Exchange—they ask, “What do they pay you?” I can feel my face fall toward gravity when I answer quietly, “Well, nothing.” They are not impressed.

“You need to get paid for your writing,” they insist. I know it’s true, but I also know that I need to start building rapport with those in the publishing industry before I can request payment. Plus, I love what I do, which is sharing stories about raising Felicity and Sarah and what I am learning about myself by being a mom.

Catholic media was a natural outlet for me to begin expressing my thoughts beyond my personal blog, Love Alone Creates. Faith colors everything in my life and has been my guiding force in navigating Sarah’s diagnosis—and in unraveling my grief.

I’ll tell you how I suspected it was grief and not depression: because I found ways to function and even find pockets of delight during those first weeks after Sarah was born. The feeling upon me is not hollow exactly but more of a shower of sadness related to some undefinable loss. Criteria for Major Depressive Disorder are specific and pervasive, but what I feel inside comes in waves.

My family physician at this time, Dr. Nush, rushes to prescribe me anti-depressants when I share with him how hard it is for me to accept that Sarah is going to endure a life of hardship. I tell him I’m not ready to travel down this path, and he reluctantly agrees. That’s when I begin asking myself, What is this then? Could it be grief? How can I know?

At home, in between blogging, I scour the internet for books about grief, but nothing settles with me as fully accurate in describing my own experience: I’m not dealing with a clear tragedy, like cancer or a car accident or losing someone to physical death. It’s more like raising a medically fragile daughter has become a series of invisible deaths. Death of a dream. Death of what I’d hoped she would be. Death of a life I imagined we’d share as a family.

My editor on Catholic Exchange, Michael, emails me after I’ve been writing articles about the spirituality of grief (as I know and experience it) and asks if I am interested in writing a book. Shocked, I don’t know how to answer him. He says the articles I’ve been writing resonate strongly with his readers, and he notices a thematic thread connecting each of them.

I don’t want to write about grief. My childhood dreams of becoming a published author surface as I consider his offer and tell him I’ll think about it. He says sure, give it a little time, and let me know when you’re ready.

But I am not sure I will be ready to write about grief. It’s a topic that’s so…well, heavy. And hard to define. And often misunderstood. I’m no Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. I have no expertise in the area of grief, and really, it’s not a popular subject. How will I sell a book about this? Will people even want to read it?

As I deliberate the idea of writing a book about the spirituality of grief, I remember that in graduate school, I ran a grief group for teens. It wasn’t what I’d chosen to do with my unpaid internship but rather was an activity thrust upon me by my on-site supervisor, Cleve, who basically said, “None of us have time to do this, but you do.”

What he meant was that the school where I’d been assigned was the largest in our city, with a little over two thousand students. There were five school counselors who managed two thousand kids, and I don’t mean in a therapeutic way, either. They dealt with scheduling, graduation requirements, credits, diplomas, and making sure kids stayed on their academic tracks.

Because the school had experienced an unusual number of deaths in short succession the year I interned there—the double suicides of their swim coaches in a Romeo-and-Juliet scenario; a couple of student deaths related to gang violence; several young girls who had abortions; a teen couple who’d lost a baby due to SIDS; a parent of a well-known student on the swim team who had died of a heart attack while in the stands at a swim meet—the school was in crisis.

And I was the newbie assigned to handle the task of walking with teenagers I barely knew, or didn’t know at all, in their darkest pain.

Did running a three-month grief group for adolescents qualify me to write an entire tome about grief? I don’t feel confident in that, but it is at least something that adds to my experience. Still, I hesitate.

Then, a friend I’ve been speaking with for weeks who does life coaching, Eileen, texts me one afternoon and says, I think you’re supposed to write a book called From Grief to Grace. She isn’t privy to the invitation I received from Michael about writing a book about grief, but I believe in serendipity, divine intervention, providence, whatever you want to call it.

To me, this is a clear signpost pointing me in the direction of writing the book I don’t want to write or feel I am equipped to write.

Knowing nothing about the literary world, I ask Michael for advice on what to do for next steps. He tells me I need a book proposal with sample chapters and an outline, so I return to the online spaces where I already write and request help from other published authors on how to go about doing this.

Maybe because I have been writing regularly for these websites, maybe because I have also read and reviewed several authors’ books, maybe because I connected with a handful of them in a personal way, I end up with a template for writing a book proposal from a well-loved and established Catholic writer, Lisa Hendey.

After drafting the proposal for what the book on grief will look like, I submit it to the acquisitions editor at Sophia Institute Press, where my editor Michael works. I don’t know what I am doing. At all. And I convince myself that I will receive a polite rejection. So I wait. And eventually, after a couple of weeks, I forget about it entirely.

On a cold January morning, after dropping Felicity off at preschool, I drive home admiring the rare sunshine and clear blue winter sky. In an instant, while on the stretch of highway between Goshen and New Paris, a clear thought pops in my mind: Check your email when you get home. You have an offer to sign a contract for your book.

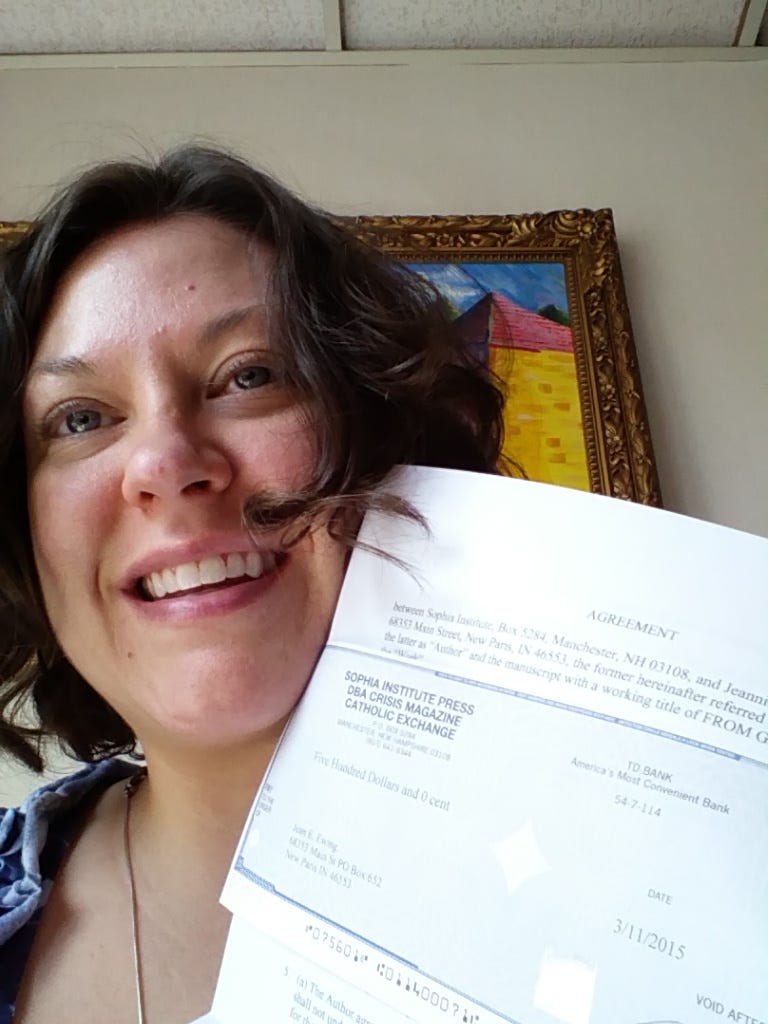

Without any evidence whatsoever, I accept this as truth. I just know. It’s something that has happened to me a few times in my life—this knowing—and it’s happening again. When I return home and check my email, sure enough, there’s a letter from the publisher of Sophia Institute Press, saying he loves my book proposal and would be delighted to publish From Grief to Grace.

Substack writer

shared with me not long ago this testimonial about why she upgraded her subscription, and I felt deeply humbled by her story. It made me realize that none of us ever truly knows the impact we have on others in a personal way—the way we might have changed their lives in a pivotal moment, during a terrifying event, while feeling despondent. My daughter Sarah is one of those people who naturally reaches straight into people’s hearts without even trying. I am honored to be her mom and to share her life with all of you. And she tells me all the time how much she loves our “Substack friends.”Your financial contribution helps supplement our family’s expenses and offset the costs of ongoing medical care for our daughter Sarah that requires 20 hours of unpaid caregiving on my part. I want you to know how much your support means and how it helps our family.

Jeannie, I think you know a lot about grief from your writing as well as love and healing and giving. Losing something one hopes for is powerful and that includes the loss of feeling in control of your life. Seeing a child suffer through procedures is crushing!

I lost my 35 year old son to stage 4, gastric cancer. He was loved by everyone he met and worked with. I gave up my job and retired to move to Florida to be with him through surgeries and chemo.

The grief was unbearable- to lose him, my career, my friends, my everyday life. It was a hard 14 mos but the right place and time to be as time was short.

I t would have been easy to just stop living and experiencing joy but I have two other sons and two grandkids. I have read that when walking through hellfire just keep on walking to get through it. After two years of putting one foot in front of the other and continuing to live I now feel joy and peace along with the grief and pain. His loss is a wound that will never heal but I am glad for each day. He lives now through my heart and memory and that is precious.

Hi Jeannie,

This is such a poignant story, and I can totally believe you were made to write this book. So many people don't have the opportunity to let their voices be heard, but you have the talent and grit to do just that!