The Park beckons me to return for memory’s sake - not for harm, but for healing. So I do return, again and again. There’s something about it that lures me back to a time in my life when I rode my bike on this same worn path, carefree and clueless. The Park does not force me to listen to my past, but instead kindly whispers to my heart through the trees now decades older than they were when I was a child: “I’m still here.”

Sarah and Felicity beg me to take them here, though I prefer to go alone. I relent, because this is their legacy, too, and it has the potential to become their own type of refuge as their lives take unexpected turns.

“Why did you come here by yourself?” Felicity asks, referring to the few vague recollections I share with her about what The Park meant to me when I was a little girl. I trail behind her. She rides her bike with alacrity, and all I can muster in reply is, “It’s complicated.”

She seems satisfied enough. Still, I offer more. “It might mean something special to you, too.” She does not react but pedals faster, carried by the tailwind that eases her ride.

As a child, The Park was where I would retreat from the suffocation of home. It was a place I could think, undisturbed. A place that was usually quiet. The vast field that lay between the tennis court and the playground offered my mind a reprieve from constant worry, frustration, and confusion.

Most of my memories of The Park take me to when I was about ten years old. I would arrive swiftly on my bike but leave at a slower pace. I guess it was my safe place before there were such things.

Felicity’s already flying free, light years ahead of me. My age has slowed me, maybe so that I can ponder and to notice things again. But she, in her youth, carries stealth and speed, with the wind behind her and everything she cannot yet determine in front of her.

Sarah, who likes to walk by my side, mutters to herself, as usual. I’ve come to understand this is how she best processes what she is learning. She’s been practicing pronunciation of new vocabulary words, and I rarely do much more than tune her out. Because of her recent autism diagnosis, I realize I can’t follow every word or sound she makes at every moment, because sometimes it’s all nonsense.

To me, anyway.

Sarah takes the journey to The Park as my companion, then decides to join her sister when we arrive at the entrance, still weathered from the construction of a concrete path poured decades ago. The girls frolic, as young children do, and I saunter around the concrete pathway, musing about how my life has begotten theirs. We ended up in this same space somehow. We are sharing in the act of time’s passage from then to when.

On the walk home, I can’t make out the words Sarah mumbles, and I don’t pretend to try. She doesn’t notice, or doesn’t care. But these six words I distinctly hear her say: “Life is like a thousand sorrows.”

Did I miss something she said while we traipsed the block from our home to the playground? Had I become so accustomed to tuning her out that I didn’t catch the context of what brought on this profound, stunning statement?

“What did you say, Sarah?” I asked, only to be sure I hadn’t misunderstood.

She repeated, “Life is like a thousand sorrows.” Matter-of-fact, as if to say, who doesn’t know this?

“Where did you hear that?” I was half incredulous, half breathless from walking at a faster clip to keep up with her.

She shrugged. “I don’t know.” She glanced at me, beaming, that enigmatic sparkle in her eyes that meant something I couldn’t reach. With that, she sprinted toward Felicity, who was patiently waiting by the curb to cross the street to our house.

In an instant, Sarah went on with her day. She did not spend hours ruminating on what she said, where she heard it, or what it meant. To her, it was an obvious declaration of life. To me, it was poetic, eloquent. She stunned me with her ability to grip the human heart and never realize she did it.

To be so simple in her ways, yet demand radical honesty - and profess it unabashedly - wasn’t this the buried treasure for which we all search, often fruitlessly? Most of us complicate things. We churn them over and over until we can make them intelligible, even impactful, unique.

But Sarah, in six words, gives me fodder for days, even as she sifts through sand in the sandbox with Felicity and asks me what’s for lunch.

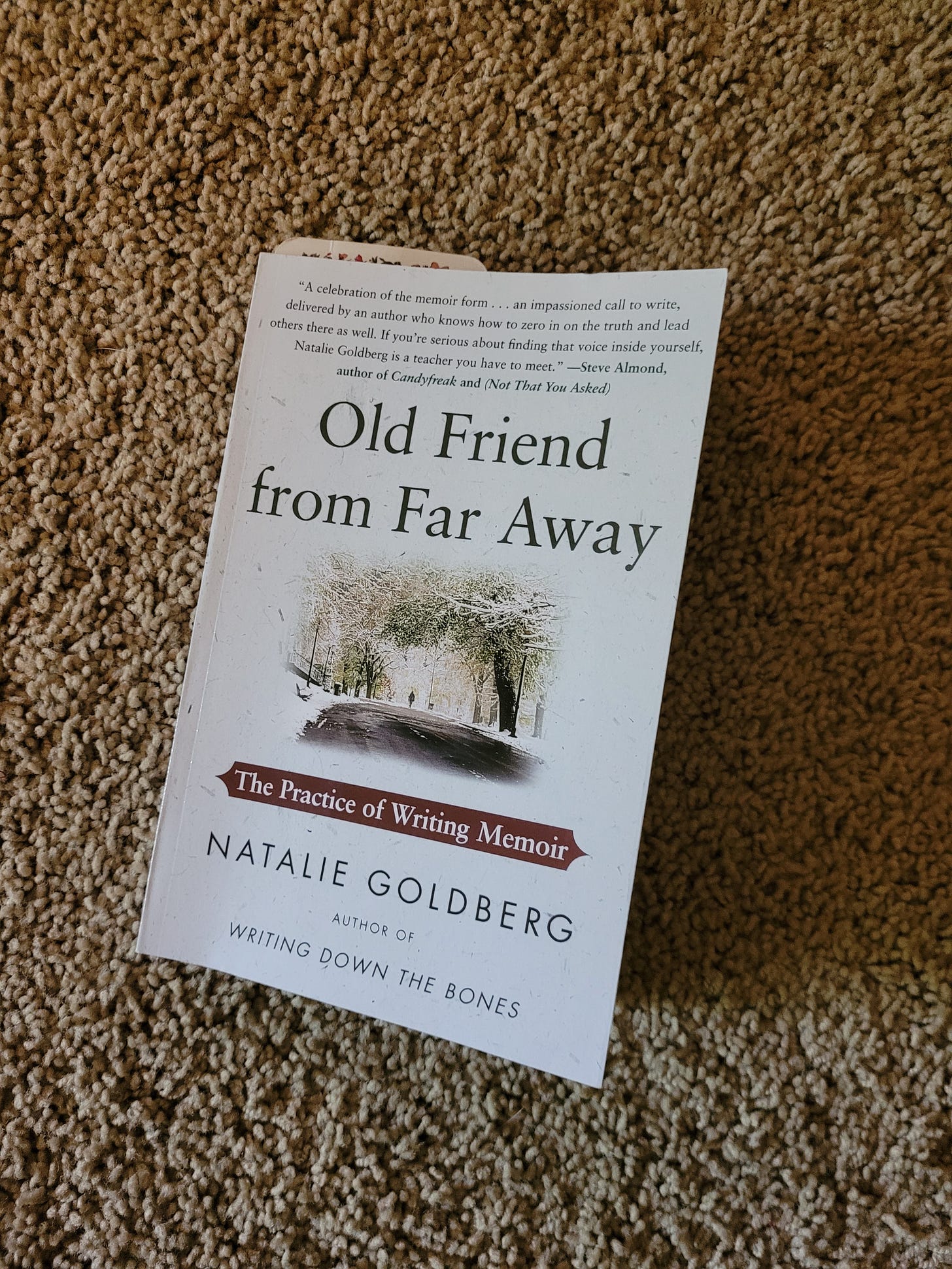

What I’m reading:

I had not heard of Natalie Goldberg, or her workshops or her writing, until a few months ago. Since then, I have read Writing Down the Bones (with plenty of dog-eared pages and sticky notes) and am working my way through Old Friend from Far Away. Even though I have always considered myself a writer of the heart, Natalie challenges me to dig even more deeply than I already am. She reminds me that writing is a practice, a discipline, and an art. It reveals the psyche and the soul.