You don't lose hope, because you can't.

Hope reminds you that life is fragile and ferocious and isn’t really yours to give and take away.

Our daughter, Sarah, was only six months old when her skull was surgically severed - a necessary, life-saving operation, we were told.

When she was born, her face and body revealed the telltale signs of the genetic anomaly she would be diagnosed with called Apert syndrome. Her forehead protruded well past her eyebrows. Her asymmetrical head formed a flattened, vertical cylinder. Her eyes bulged from their sockets, imitating the emotion of shock or fear. Her fingers, indistinguishable from each other, fused into tiny mittens with a sheath of smooth, supple skin concealing the bones and cartilage underneath. Her feet presented as flat and wide, with webbed toes.

Medically, the fusion of these digits is known as syndactyly and would require careful surgical separation in order for Sarah’s hands to function somewhat typically. But her skull, which had become calcified and hardened before she was born, was termed craniosynostosis, and was, of course, of more urgent concern.

It was the soft spot on a newborn’s head that made me shudder when a mother offered for me to hold her baby. What if I accidentally crushed it, or the baby’s head slipped and my thumb pressed into it too hard? The fragility of what housed the primary operating system for a human’s life seemed too heavy a responsibility for me to hold.

But Sarah had the opposite problem. Her skull had no pliability, no tender membrane that would gently stretch as her tiny brain grew at a rapid pace that first year of life. Because of this, her craniofacial surgeon warned us that, if we did not schedule the operation to open the fused sutures as soon as possible, her brain could become crushed inside the already-formed skull.

In moments like these, you are stunned to learn that life itself is not as malleable and forgiving as you had hoped or once believed it to be. My infant daughter, who at the time did not know pain beyond occasional stomach discomfort or cold rain on her nose or bright sunshine beaming in her eyes, would bear a pain I could not share with her.

The neurosurgeon would carve her bicoronal plates open, once her hair was shaved and the flesh of her head had been sliced with a scalpel. Once inside, the craniofacial surgeon would insert a metal distraction device, partially internal and partially exposed at the temples. The exposed portion included two tiny screws, which Ben and I would be responsible for rotating with a medical screwdriver every day for about a month.

The purpose of this device was to gradually open up the plates of Sarah’s skull that had no way of expanding on its own, in order to accommodate her developing brain. Without this procedure, she risked severe and irreversible brain damage, or worse, death.

It was the only way.

Though Ben and I were confident in the skills of Sarah’s surgeons, our hearts shattered when we realized that, once the initial pain medication wore off, her head and face would swell and throb and she would not understand the source of this agonizing pain. All we could do was hold her, administer her oral pain medication, and keep her as comfortable as possible.

You lose a part of yourself when your child must suffer something you cannot prevent or reduce or eliminate.

You lose the ability to be cheerful when passersby pause and comment on your “adorable baby.”

You lose the capacity to smile when your neighbor laments that her perfectly typical, perfectly healthy toddler “might be sick with a slight fever.”

You lose your composure when a friend asks if you are well and adds, “I’m praying for Sarah.”

What you don’t lose:

Hope and its cousin, Perspective.

You don’t lose hope, because you can’t. It’s crucial for surviving this sort of interminable winter, in which everything crumbles and decays and falls silent. You wait. But the waiting is not pleasant, not even remotely. It is a tense sort of waiting, in which you straddle the space between hope and fear.

Both of these - hope and fear - comingle, and for the first time you allow them to alight upon your heart, because what choice do you really have? Your infant’s innocence will be stripped far too soon, and not by choice. Well, by your choice. In which you feel you truly have no good option.

You will doubt. You will question. You will rage. But you return to the mystery that drives you to believe that Something Greater exists beyond this horizon of trouble. Hope is not certain, but obscure. And it is your lifeline in times like these.

The possibility, for all of us, is this: when life pummels you with wretchedness and you believe you simply cannot continue forward, somehow you do. Somehow, you find a way. It’s not that “your hands are full,” but that your heart is filled with cracks where the light still filters through, inexplicably and inexorably.

Sarah’s first major surgery is now a faded recollection I have tucked away. But I have not forgotten, and I never will. What I lost felt more onerous than what I gained, but when you gain hope and perspective - even if that is “all” it is you attain - you treasure it.

Hope changes you. It alters the way you engage with the world. Every time you find yourself slipping into frustration over your toddler son’s meltdown at his missing green plastic fork, hope gently nudges you, reminds you that life is fragile and ferocious and isn’t really yours to give and take away.

What I’m reading:

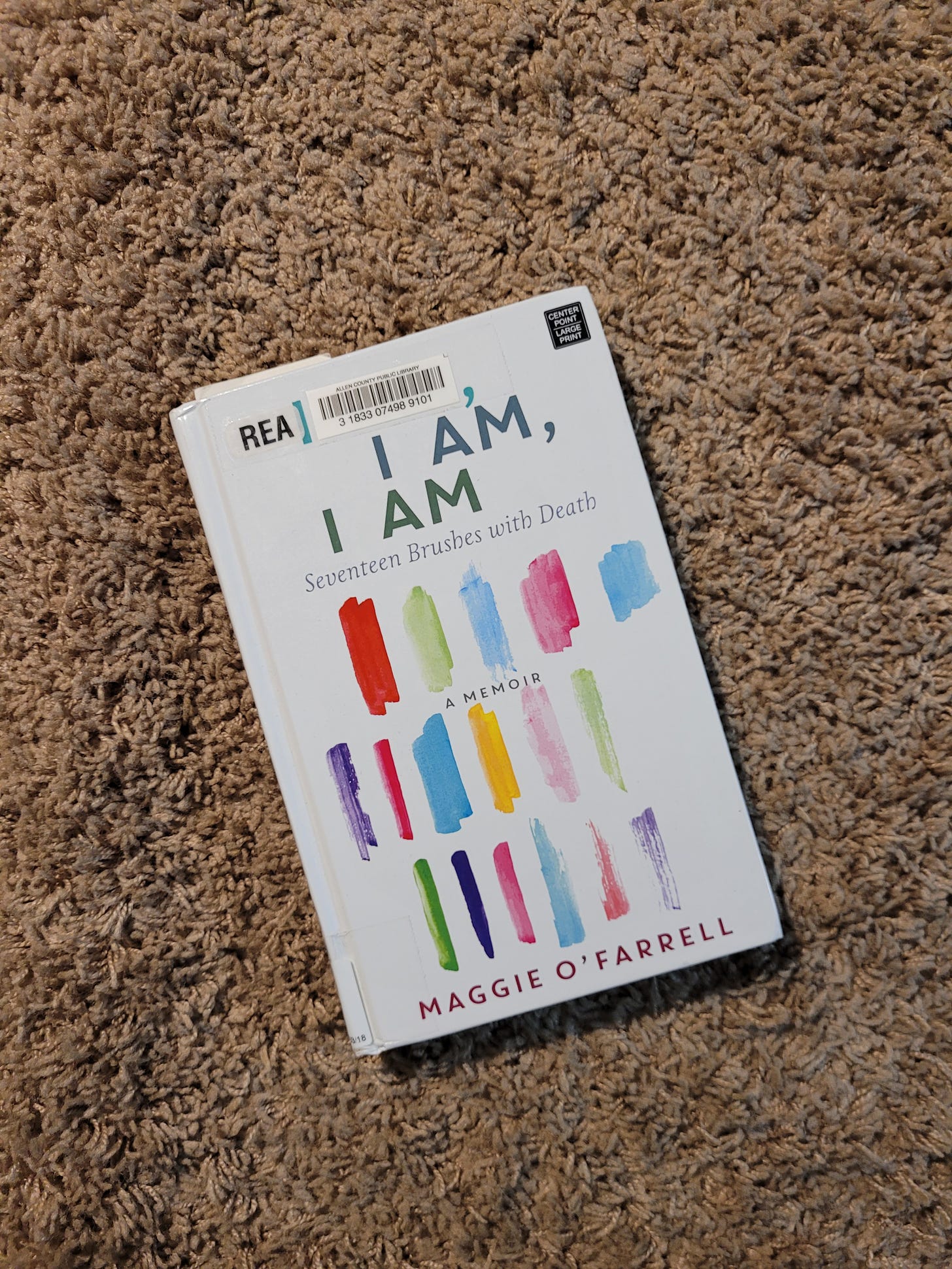

I was not familiar with Maggie O’Farrell’s work before peripherally hearing about her memoir, I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death, but this collection of essays is gripping and brutally honest and written in gorgeous prose with excellent vocabulary. There were two that made me pause more than the rest: one about miscarriage, in which her description of losing a child and all the complexities of an early loss gave words to many, many women’s experience; the other was about the birth of her first child and a botched cesarean, which gutted me. I saw myself in her words.

This testimony is so real, honest, and beautiful in so many ways. I appreciate how you share your innermost thoughts and emotions that deeply touches the sometimes painful human experience. What you have endured as a mother is different than most, but still speaks to everyone in their own way. To those going through similar experience, this is a gold mine. Thank you, Jeannie, for being brave enough to speak and write your heart. Hope is definitely here.

Woo. This one broke me to my core. Maybe a story for another day but my daughter needed brain surgery at age 2 and had a soft spot that had never closed due to a cyst in its place. She’s almost 12 now, and this story catapulted me right back into that operating room where we chased our barely toddler around for hours waiting for her surgery to finish. Well done. This was beautiful.