I allow myself to write drivel, too. Sometimes I tell myself while journaling, This is garbage, but then I keep going. I don’t stop to censor what I’m putting on the page. The reason is that I know, after ten solid years of doing this, that it’s not what I write that counts as practice. It’s how often I write and what I learn that improves my skill.

“Out west, I grew up hearing that ‘everyone wants to be a cowboy until it’s time to do the cowboy shit.’1 Maybe it’s time for you to think of it this way: In order to be a writer, do the writer shit,” Ben tells me one day, interrupting my monologue about how hard it is to become an accomplished writer.

My complaint stems from starting over. The niche in which I built a small following—writing about the spirituality of grief—didn’t involve much heavy lifting. I mean, I wrote. Furiously. Prolifically. It took me maybe three years to establish relationships with editors and other writers in my niche, and after that, obtaining work (speaking gigs and freelance offers) required very little effort.

“I know,” I tell him grimly, “but I don’t know if I will ever break through the larger industry. Access to other writers is limited. Most of them have gatekeepers—agents or publicists or managers—and they’re too busy to develop a peer-to-peer relationship with me.”

“Just show up,” Ben says. It sounds so easy, so simple. It’s something I do, anyway, but it seldom translates into fruitfulness. Meaning, I am not landing new speaking engagements, not invited to write essays and op-ed pieces by editors, like I used to. I realize, with rising dread, that I will have to actively pitch (read: market) my work if I want to get published on larger platforms.

I am terrible at selling anything, let alone myself and my skills. It all feels too vulnerable, too out-in-the-open. And I’m terrified of the inevitable rejections, because they still—still—feel personal.

That said, I can’t get outside my head most days. My inner critic has become a gnat: annoying, buzzing in my ear, persistent. I can’t get rid of it. It tells me that I was foolish to make this radical change in my creative work when inflation hit our family of seven really hard. I had an income before I walked away. Now, there’s very little streaming in from my writing. I feel defeat, doubt.

Ben rallies for me now. “You’ll get there, Jeannie. You can’t quit when things get hard. You’re not like that, anyway. The saying I grew up with means to me that people on the outside tend to romanticize what being a cowboy is like: riding around mountain landscapes on their horses, leisurely strolling on their ranch. People like the cowboy hats and old westerns and the things that cowboys symbolize to them. Maybe it’s the American Dream or a vigilante fighting the bad guys.

“But the truth is, being a cowboy is hard. It’s about shoveling shit and getting dirty and working long hours and hardly ever getting a break. Or getting paid much. That’s the reality.”

I think I understand what he’s telling me. “So, you’re saying that people also idealize what it means to be a writer, until it comes down to doing the actual work?”

He nods. “You’re in the thick of revising your first memoir. You’re drafting newsletters on Substack. You don’t hold office hours, and your friends don’t really know why you hole yourself up with a notebook and pen or a laptop to do what you do, when they don’t see the results of that…yet.”

I don’t respond. I’m mulling this over. Ben notices, pats me on the shoulder, and reminds me one last time before walking upstairs to his office, “Do the writer shit.”

There’s weight in those four words, but also encouragement. Putting in the necessary work involves grit, daily practice, and a dose of faith. It’s about stamina, about mindset, about focus. The cognitive aspect of “doing the writer shit” is my weakness, because reframing adversity doesn’t come naturally to me. I have to work at believing in myself, in my voice, in the message I share.

Over the last four years, I’ve returned to a growth, rather than fixed, mindset. I’m recognizing ways I attempted to control my life, by sticking to a stringent belief or idea. Doing this protected me from facing the ascending discomfort of admitting or expressing my rage, my anguish, my fear that (some of) the beliefs I once held so close no longer fit my life or my family.

This started with Sarah’s birth. I questioned everything I believed was true. It’s taken me over ten years to get to the point where I can sit with the tension of holding two opposing feelings simultaneously, where I can welcome the discomfort—knowing it will pass—and become curious about what my thoughts, feelings, and experiences are trying to tell me. That’s a growth mindset: curiosity; a reckoning or awakening within; movement in strange and unfamiliar directions.

Grit entails a growth mindset at its heart. I remember listening to Angela Duckworth’s book, Grit, when it was first released, and it both captivated and motivated me. Her definition of grit is this: perseverance + passion. Which means we persist through the setbacks and hurdles of attaining a particular goal that aligns with what we love or deeply desire.

What struck me most about Duckworth’s research is that the concept of talent is a misnomer. Many of us learn that some people exhibit great talent (e.g., musical prodigies or professional sports figures), while the rest of us remain just average. It’s a form of destiny, of fate, we tell ourselves. Duckworth wrote that what makes a person excel in any area of life is grit, not some rare gift. It’s about practicing, usually for thousands of hours, the mundane and tedious drills related to the end goal. The writer shit, in my case.

This segues into the daily practice portion of doing the necessary work to achieve what we want. I consider writing in any form part of my daily practice. Let me explain that, as a mom of five (including neurodivergent kiddos), I don’t always get to spend an hour or more penning eloquent insights in my spiral notebook. I used to think that’s what it meant to be a “real” writer, because I, like many others, erroneously thought real writers spent months holed up in remote cabins to complete their novels using the funds from their grants or fellowships.

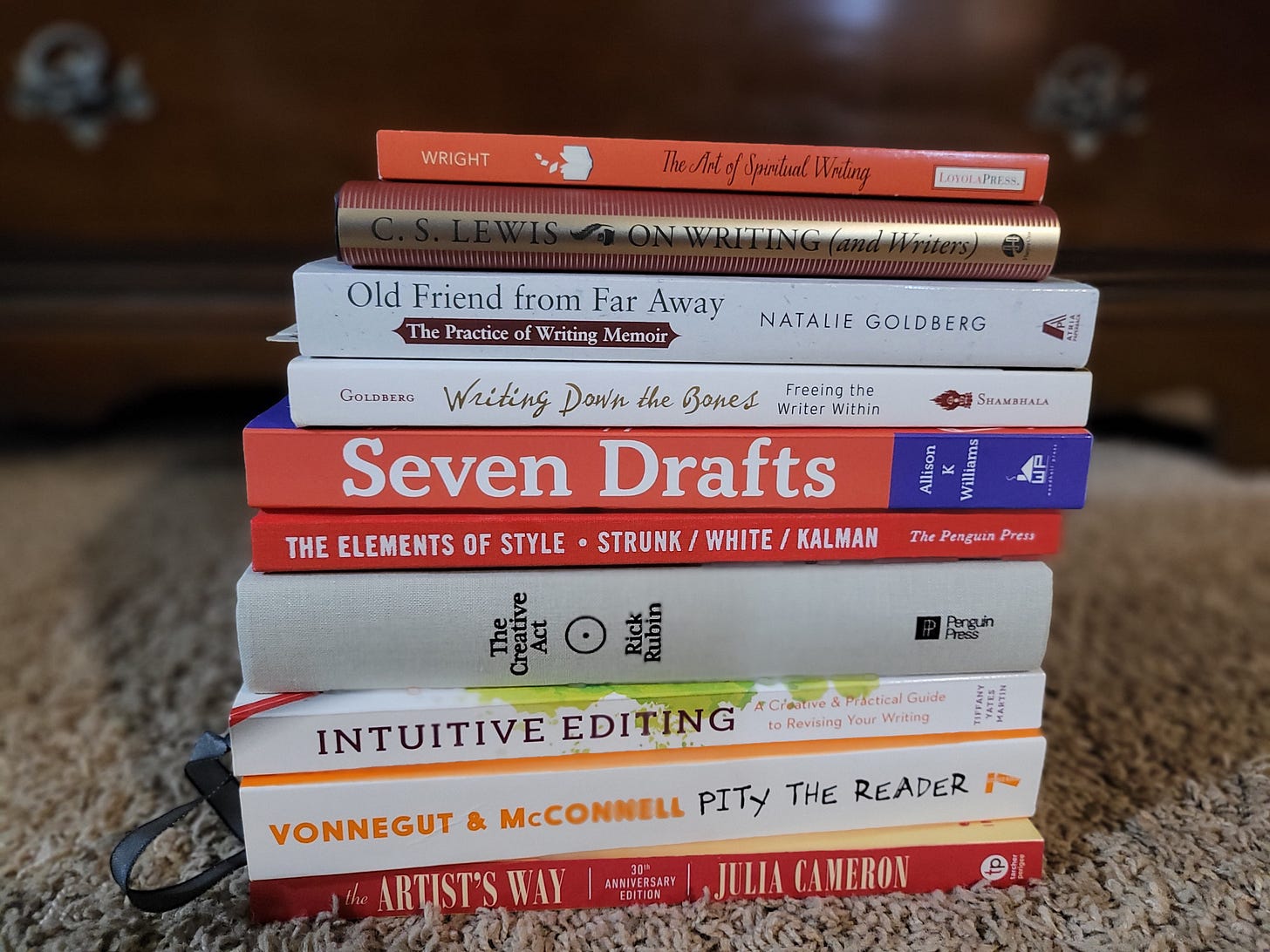

In my case, writing as a daily practice might simply mean I make a list of new verbs I want to incorporate into my memoir, in order to freshen it up. It might be scribbling nonsense (brain dump or stream-of-consciousness style) in my journal. It might be, as it is today, sitting down to intentionally craft a coherent message on my blog, or even revising three full chapters of my book. Sometimes it’s listening to a recording of a workshop and taking notes on what I learn. And reading. Always reading, sometimes a work of narrative non-fiction, sometimes a book about the craft of writing or editing.

I allow myself to write drivel, too. Sometimes I tell myself while journaling, This is garbage, but then I keep going. I don’t stop to censor what I’m putting on the page. The reason is that I know, after ten solid years of doing this, that it’s not what I write that counts as practice. It’s how often I write and what I learn that improves my skill.

Finally, the dose of faith is about believing in something that hasn’t fully taken shape yet. It’s about pursuing my passion without knowing with certainty that I will achieve it. I revisit a few reminders when I feel myself slipping into discouragement:

No one can write my story, except for me.

My voice is my own, and no one else writes exactly as I do.

My writing will improve if I keep practicing.

All I need to do is the next step in front of me: revise a chapter of my book, edit a blog post, finish my editorial calendar.

Faith is confidence. It’s trusting that my efforts today will compound into something I don’t realize is taking shape for tomorrow, or ten years from now. There is no solid evidence for faith, which is the point of it, anyway: to simply believe in what I am doing and to continue opening my mind and heart to whatever nudges me. To create something from nothing, then modify it, then accept it when joy springs forth in what I observe about it.

To paraphrase Benjamin Dreyer,2 my work will never be finished. I can only stop working on it at some point and let it be what it is, even if it is incomplete or imperfect.

In that case, doing the writer shit, for me, means allowing myself to be human and for that flawed form of myself to show up today, every day, and press on.

Attributed to Ross Cooper from his song, “Everybody Wants to be a Cowboy.”

Dreyer, Benjamin. Dreyer’s English: Good Advice for Good Writing (Delacorte Press, 2021), p. 265.

Jeannie. As a priest, I can tell you, using your own words, Catholics have to do the faith "shit" every day. People who are either new or very superficial in their thinking think that believing in God is all about consolations and feeling good. Faith is about the cross. It is about believing in God's love and presence when you are so tired, angry or fed up with God, the church or others that you want to just give up. Faith is the awareness, recognition and acceptance that God is with you especially when things are empty and you are falling behind or getting beaten. I would recommend having a crucifix nearby when you are writing. God is using the world to write on your soul, and your soul is not paper that will take lead or link. It is stone that has to be chiseled. Hope to talk to you on DRIVING HOME THE FAITH SOON. Fr. Rob Jack

How true. Letting go of the end goal and focusing on the joy of the process (in painting as in writing) was a game changer for me personally. But you're right- it's a routine like anything else, like working out... It's work.