On beauty culture and body neutrality

It's easy to fix your face, but harder to change your heart.

It’s easier to fix your face, but harder to change your heart.

For an audio version of this essay, please click here:

I was around age ten when I started worrying about my weight.

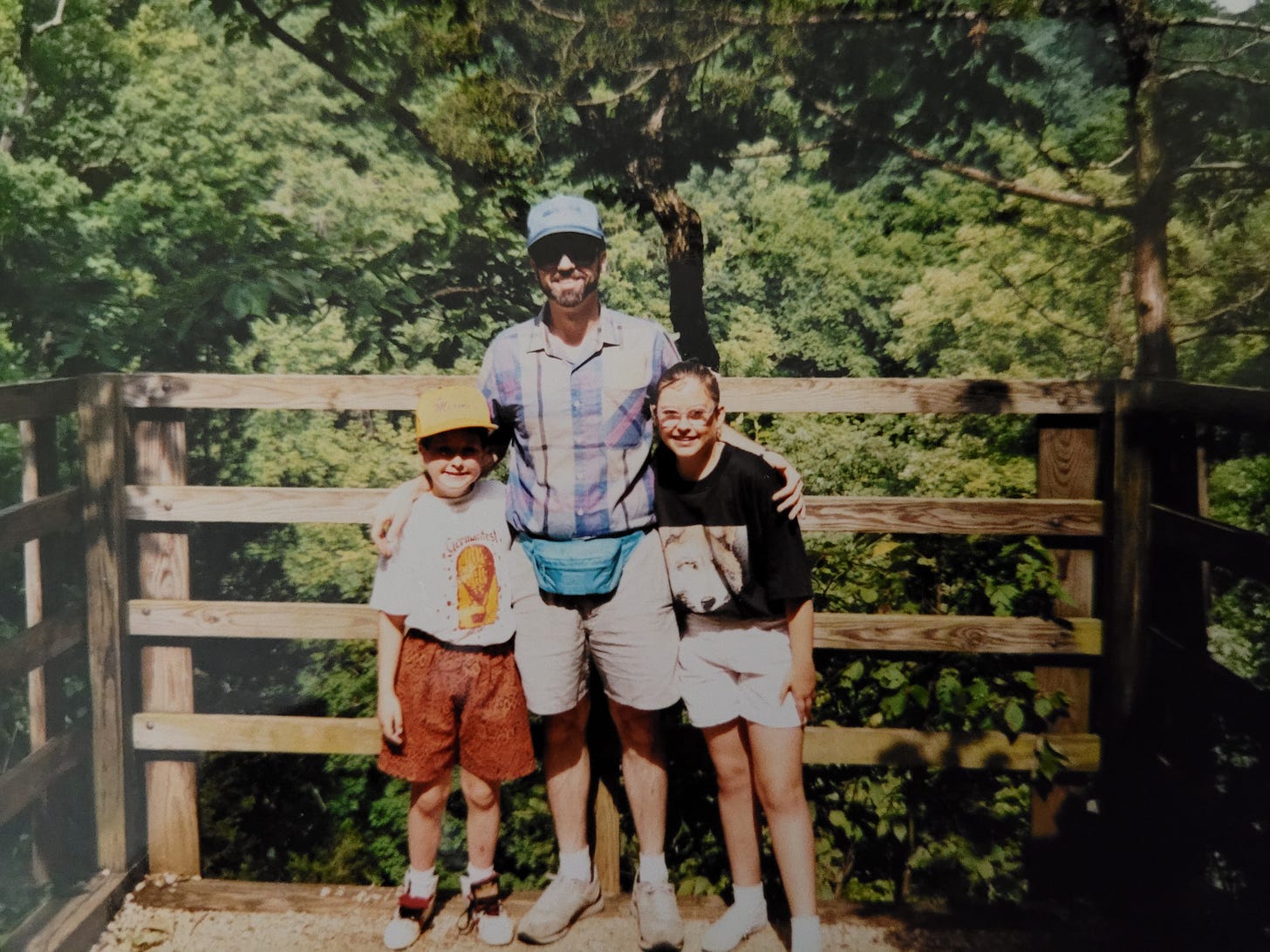

I exited our silver Ford Aerostar on a sunny afternoon, my mom following behind on our winding walkway to the front door of our house. I was short(ish)—about four-foot-ten—with Coke-bottle glasses that slid down the bridge of my nose, a mouth full of metal braces, and mousy brown hair. At the time, the parts of my appearance I scrutinized were restricted to everything above the neck.

That is, until that day.

I had a well child check-up, and my pediatrician had lightly scolded my mom, “Try to watch her weight.” He didn’t speak to me directly, as was customary in the 80s, though I was old enough to instantly absorb the shame related to his words. My mom didn’t say anything as she escorted me back to our vehicle, but once inside the van, she said, “You need to lose a little bit of weight. That’s what Dr. Steigmeyer just said, so let’s keep an eye on how much you eat, okay?”

As a child, I didn’t know how to respond, so I just said, “Okay.” This is what I always said to my parents (or any adults) when they asked a question that was really a statement. I knew there was nothing I could ask or protest, but I felt awash in sadness. What was wrong with my body? My weight? What did it mean to ‘watch’ my weight, or ‘lose’ weight? And why?

The only truly obese people I’d known were on my dad’s side of the family, but my parents rarely spoke about their bodies (to their credit). Just once I recall my mom telling me with pity that she felt sorry for Aunt Jackie, because she was so overweight. At age ten, I knew I wasn’t fat. I guess I wasn’t skinny, either, but I didn’t care until the moment I walked out of that appointment and into our house.

From then on, every time I ate, I deliberated: Should I eat this? Is it too much food? Will it make me gain weight? This kind of thinking stripped the joy out of eating, because I was preoccupied with what food would do to my body, rather than enjoying how food tasted, eating until I was satiated, and focusing on the nourishment my body was receiving.

I didn’t grow up exclusively on chips, cookies, sodas, or processed foods. My mom carefully doled these out as occasional treats, and she did so with clear intention. Her mother was diagnosed with Type I diabetes as a child in the 1930s, and my mom didn’t want my tastebuds to be conditioned towards preferring sweets.

Still, I felt guilty every time I was at a summer barbecue or stayed overnight at a friend’s house. Pizza? Dr. Pepper? Ice cream? Should I, or should I not? It was a cruel game of tug-of-war, and it never, ever relented.

I never forgot that my body didn’t conform to societal standards. I couldn’t. As a teenager, each time I accompanied my closest friends to the mall when they wanted to try on clothes, I sat outside the waiting room with dread filling the pit of my stomach. Never did I dare to ask them if a particular pair of jeans flattered me, because I was a size 12. Horror of horrors when your friends are groaning about how they’ve “gone up from a size four to a six.”

Often, boys at school would waltz up to me and, without saying hi or acknowledging me, simply ask, “Where’s your blond friend, Amy?” That’s who they wanted—my blond friend—never anyone else. The fact that they referred to her this way sent an obvious signal to me that being a brunette meant I wasn’t going to garner as much attention from boys. And I didn’t overall.

The message was clear: thin waist, big breasts, and blond hair. That’s what makes a woman attractive.

By the time I met my husband Ben at age 25, I had accepted the reality that my figure, curvy though it was, did not make me a physically attractive female. So I concealed it as best as I could, wearing high necklines and loose t-shirts to hide my breasts and small tummy bulge. I had thick thighs, too, so I wore modest-lengthed shorts that ended just above the knee in summer and jeans with baggy sweatshirts in the winter.

I kept myself small, because the baggage of body shame bogged me down. I was an ox dragging its onus, and this invisible, emotional load prevented me from recognizing that my appearance was the least important or interesting aspect about who I am. Low self-esteem, insecurities in romantic relationships, and lack of confidence were the cloaks I wore.

The fact that Ben loves all of me, through all of the changes my body has been through since we first met, still baffles me. But at least now, in midlife, I am learning to accept myself and the body I inhabit.

In recent months, I have learned a couple of things about body image:

The term “body neutrality” appeared on my Instagram feed a while back, and I took a screenshot of the meme in order to remember the term. Body neutrality refers to a middle stance between body shame and body positivity, in which we neither work hard to love our appearance, nor revel in loathing over our perceived flaws. Instead, it’s a means of making peace with the way you are, accepting the reality that you have wrinkles or grey hairs or stretch marks or saddlebags (I am referring to myself here) without trying to change how you feel about them. They just are. They exist. Our bodies tell the stories of our lives—what we’ve been through, who we’ve become, and how. Allowing yourself to be accepting without rejoicing over every aspect of your body is one way to move away from abusive self-criticism.

- has written about body acceptance, and in one of her monthly gatherings on Zoom, she shared an affirmation that stayed with me: “I live in a human body, and it is normal and okay for human bodies to change.” Now, every time I look in the mirror and find myself feeling disgusted with the way my midlife body looks, I tell myself this until I believe it. Or at the very least can return to a cognitive state of remembering that my appearance isn’t the best part of me, that beauty radiates from who I am as a person.

I’ve written about how my daughter Sarah has radically changed my self-perception. She was born with a rare craniofacial condition called Apert syndrome, and she doesn’t look at all like the beauty standards tell us she should. After meeting others of all ages who have either Apert or similar diagnoses, I thought about the concept of beauty and realized that the way they live—generously, fearlessly, joyfully—reflects what it means to be a truly beautiful person.

And if that is true for people who are tormented at times or taunted as “ugly,” “monster,” or “witch,” then it applies to every human. I think it’s what my mom meant to say about my Aunt Jackie—not so much that she felt sorry for her (though maybe she did), but that she loved my aunt for her heart, her gregarious and ornery nature, her hearty laugh, her love and faith.

Each of us can claim the word beautiful to describe us, because there is an indelible imprint of goodness within us. We are each capable of magnanimity, of hope, of encouraging others, of love. We are love. Love dwells inside every human heart. I think sometimes we focus on our broken nature, because it’s easier than claiming our right to be lovely and delightful—our worthiness, our worth.

Ruminating over external “flaws,” like crow’s feet or turkey neck or muffin tops, in my view, are ways we patch the deeper wounds we tend to hide inside of us. Being vulnerable, being open with others and honest with ourselves, require a sort of startling admission that we aren’t exactly who we thought we were, but we’re still okay as we are.

Maybe even beautiful.

If you enjoyed this post, consider checking out some other articles I’ve written on this topic:

Traverse the dark places of your life: Your shadows are the beautiful things about you.

Permission to be who you are is empowering: Give voice to the truth of your life.

Who are the beautiful people? Raising a daughter with a craniofacial condition taught me to look within.

Jeannie, this line really struck me: "Ruminating over external 'flaws,' like crow’s feet or turkey neck or muffin tops, in my view, are ways we patch the deeper wounds we tend to hide inside of us." It's a really profound way to view ourselves, and I so appreciate you bringing into the light for me. XO

Your description of the confusion you felt as a child when told to “watch your weight” made my inner child feel so seen. I wish I could hug young Jeannie and young Rachel and assure them that we are so much more than the container in which our beautiful hearts, minds, and souls reside. Thank goodness we know this now and can support each other as we shed the damaging beliefs that were imposed on us. My hand in yours.